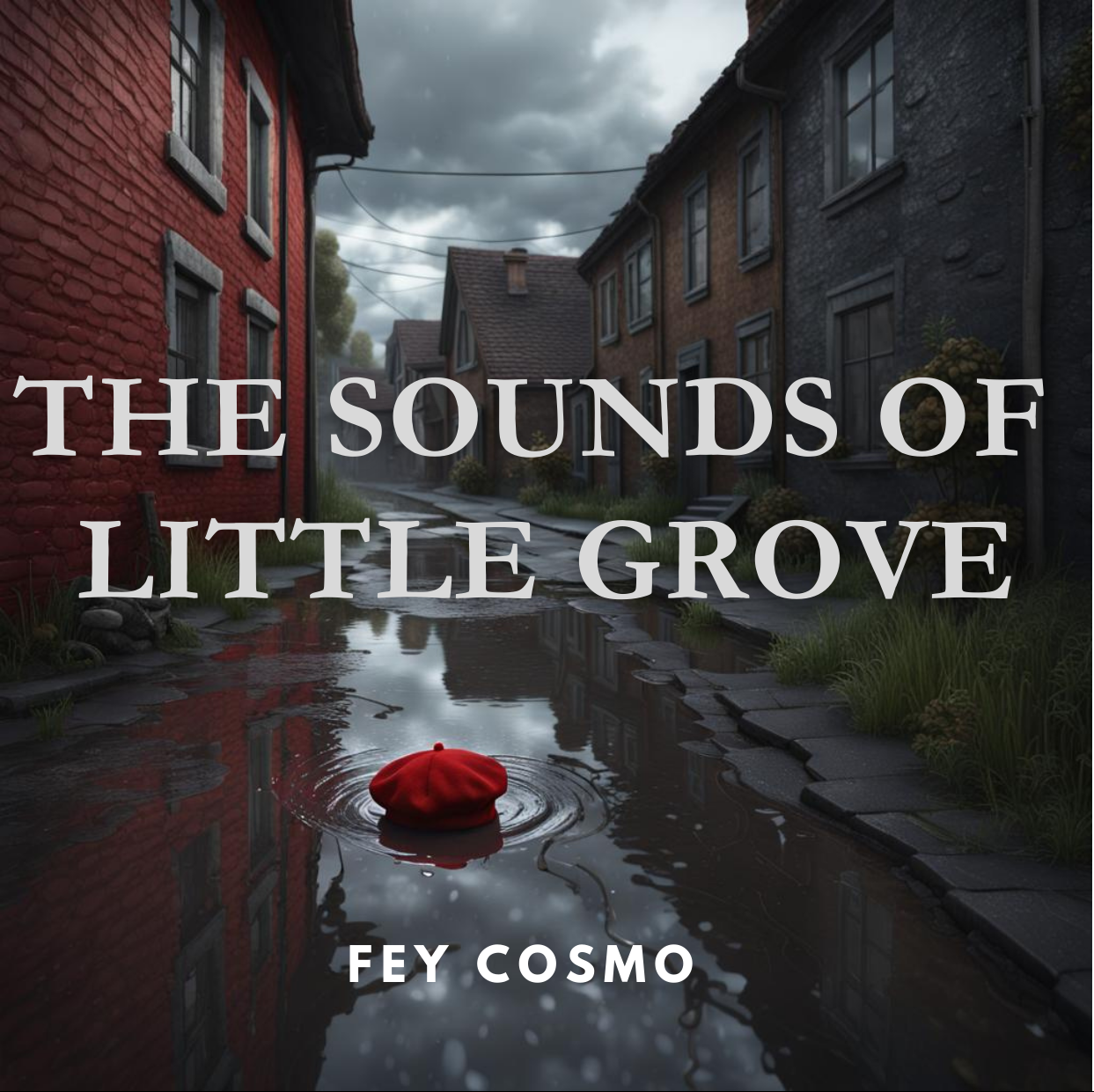

A new horror story by the Fiction Fairy, Fey Cosmo. This story is lovingly dedicated to D and M… you know who you are

TRIGGER WARNING: This contains confronting themes and is recommended for those aged 15 and up.

Dear Reader: The serial, “Brethren of Judas” is on a mental health/research hiatus, as the topic of coercion right now is a difficult one for me. Please enjoy ‘The Sounds of Little Grove’, a one-off story of modern, suburban horror.

He still walks them down the street, every evening. They’re still a snarling, horrifying mass of teeth and muscled, sleek bodies wearing studded collars. But now Killer Jap wears a scrappy, red bandana around his neck, and I dream about them.

My name is Brodie Marie Regan and I’m 14. This is not my story, it’s a story about a friend of mine called Ginevra Grace Rhodes. I’m taking a course for “Promising Young Athletes”, and this is the for the project, “Who Inspires You?” I know we were probably supposed to write about someone famous, but she Ginevra really inspired me, so here’s the story.

I should mention, our names are important because I’m pretty sure that’s why Mrs Halbrook put us together in kindergarten. Mrs Halbrook loved alphabetical order, and Rhodes followed Regan. I remember very clearly when she, Ginevra, walked in because she wasn’t wearing a uniform, she was wearing pyjama pants and a top that looked similar, but not quite part of the uniform. Mrs Halbrook would have said something, like, ‘This is Ginny, Ginny this is your class….’ or something like that, but then a small, precise voice corrected her. “Excuthe me pleathe, Thuthanna Halbrook, my full name ith Ginevra Grathe Rhodeth

Tylar Scott, who would later become the biggest jerk in our year screamed at the teacher, “MISS IS YOUR FIRST NAME SUSANNA? THAT’S A DUMB NAME!” The whole class laughed but I remember Ginevra (not Ginny) scowling, like she wasn’t 5 and a half like the rest of us. She frowned like an impatient grownup.

Soon this strange, pyjama-wearing, alien-acting girl with a giant lisp (lithp) was sitting next to me and unpacking with great care. I didn’t know what to say, she just kept pulling out lead pencils until there were about 8, all unsharpened and with their little white rubber ends completely clean. “How many do you have?” I asked in surprise. “Eight. I like the number eight,” Ginevra replied, in that same calm, precise voice. I would learn later that Ginevra really liked the number eight. In fact, when she liked something, anything, she Liked it with a capital L.

A few days later, Becky Roehampton was moved from our table of six girls because Cheryl came to our class. Cheryl was always around when Ginevra was in class, except for sport, and we simply accepted her as an adult that got paid to help kids in general, but especially to help Ginevra. She didn’t need help for schoolwork because she was very smart. But Ginevra needed help fitting in and doing the right thing. When Ginevra finished primary school with us, Cheryl was replaced by Mr Paxton, who did the same thing but in high school.

It’s funny to remember now, how much I seemed to see of Ginevra. I remember her always being there and then I couldn’t imagine school without her because she was my Friend. Friend with a capital F because she was very good to be friends with, because she always told the truth and always looked at you when you talked. Some people didn’t like that, but she looked RIGHT AT THEM, right in the eyes I mean. Sometimes other people would look away. But I didn’t mind, because it was nice to feel that when I spoke, Ginevra was hearing every word, like I was important. After a while I realised it was a bit of a privilege to be her friend, because she chose me, all because of my dad making me an egg sandwich for lunch.

My dad and me are the only two people in our family, unless you count Fancy, our poodle. Dad makes me lunch every morning and carefully trims off the crust and cuts the sandwich into neat triangles. Ginevra saw this as we opened our lunchboxes on the first day and for her at least, this made us BFF’s for life, as she TOO had an egg sandwich cut the same way. She was already sitting next to me, now we were eating the same food too. Little did I realise she ONLY liked egg sandwiches and would eat the same thing for lunch every day. Of course, the difference was who had made it, as Ginevra very precisely informed me, “My mother Doctor Thabrina Faith Rhodth made thith. She ith a doctor.” I replied that my dad Mick made mine, and I was pretty sure he wasn’t a doctor down at the factory.

Mum left when I was 2 and I don’t remember her at all. Dad tells me she got ‘fed up’ and just flew back to the UK and now it’s like she was never here at all. He always says, “Don’t worry love, she got fed up with me, not you,” but I’ll never know. I’ve seen a lot of two-year olds and they’re pretty annoying. Maybe I would have felt fed up too. I mean, look at my name! Dad was so sure I was going to be a boy he used the boy name he had reserved already. Thank GOD mum gave me the middle name of ‘Marie’ for one of her relatives. This confused my teachers growing up, as they expected to see a BOY when they called out “Brodie Regan”. But now I kinda like my name, especially when you say all three together, in a row, like Ginervra always did. To her I was never just ‘Brodie’.

A lot of people didn’t like that about her though. I know primary school wasn’t easy for her because I was there for all of it. I was there when Tylar Scott cut some of her hair off and she screamed for two hours until her mum picked her up. I was there when Morris Melunga (in year 6!) thought it would be funny to steal her Munchables right out of her lunch box, because he knew she’d scream about it. That time it wasn’t two hours though, because Dr Rhodes, Ginevra’s mother, got smart and moved to a closer doctor’s office. In our class, we learnt the term, “meltdown” and why Ginevra needed her space when it happened. Cheryl even taught me to look for “triggers” and I saw that before any “meltdown”, Ginevra would scratch her head uncontrollably. When she was calm, and older, she said it was like her scalp was on fire from the tension inside.

I started to see a lot of Ginevra’s family when she invited me to the Horse Party. In year 2 Ginevra absolutely LOVED horses. Everything had to be horses. She invited me and Sandra Lauren Thompson, but Sandra didn’t show up. The rest of the guests were her much older cousins, but Ginevra and I had a great time. Dr Rhodes had hired two ponies and we rode them around the yard for hours, even after the sun went down. At first Mr Rhodes tenderly led Ginevra around but in her normal, blunt manner, she quickly told him she was ok on her own, in her little pink cowgirl hat and pyjama pants. Eventually dad showed up looking for me, but he stayed for a cup of tea when he saw how much fun we were having. I remember having a super sore butt and thighs for days after because Ginevra just wanted to go round and round on her tired, brown pony. It’s a nice memory.

I remember very clearly when we were both nine that I started to get good at netball, and I was almost not Ginevra’s friend anymore. We learnt netball in sport and for the first time in my life I was good at something. Not a little bit good, but pretty good, and I was fast too. I got a spot on the under tens team and suddenly a lot more people wanted to talk to me. Dad was proud too. The only person who was not happy was Ginevra, mostly because she wasn’t very into sport. I mean she could throw a ball and run and everything but very quickly she would lose interest and want to go back to reading or drawing or counting or Maths or whatever else she had in her bag to do. I remember now, that at this time it was the closest I came to Ginevra not being my friend, until the day I invited her down to the court and she found something new to Love.

Love gets a capital because when Ginevra LOVES something, she loves it hard. Like in year 2 when she LOVED horses. After that it was Fantastic Crew, the tv show about the boy and his super-cat that go on adventures. Then it was computers. Then Netball rules, not the playing but the RULES. Then it was laws when we got to high school. I blame Sergeant Sam.

Sergeant Sam was a police officer who came to our school to talk about ‘Safe Fun Over the School Holidays’ because there’s a lot of crime in Little Groves. A long time ago, when the very rich ‘Little Family’ owned the land, they named EVERYTHING after themselves. Little Grove Public School. Little Grove Road. Little Lane. Little Street. Everything is called Little, even the netball courts, which are new, are called ‘Little Recreational Park’. Sergeant Sam told us about this and explained something called urban decay, which I didn’t understand, but I can remember the words on the screen of his presentation. They looked like graffiti. Sergeant Sam explained about all the things that were ‘illegal’ and ‘against the law’ and Ginevra was fascinated. I think all her life she wanted to learn about how things work and here was a way to understand the whole WORLD. Sergeant Sam smiled and looked kinda cute for an old guy and we got to ask questions and Tylar Scott wanted to touch his gun, but Ginevra was not content just with his explanation, she wanted to know more. After this she was away for a few days and when she came back, she seemed to have learnt a LOT about different laws. It was pretty impressive. “Thargeant Tham was the tip of the itheberg, Brodie Marie Regan. All the good information ith online,” she said.

I didn’t mention at the beginning… Ginevra had a really bad lisp. It never went away- no matter how much she saw “Mithuth Mulheron” (Mrs Mulheron), the special speech-teacher that stayed with her till year 5. I think they just gave up after that because they realise it would never change. To me, it was just a part of her, but a lot of people teased her. Mr Gretchen, the casual teacher, laughed when he heard her in year 4. Being a teacher who laughed at her made it ok for the kids to laugh at her, until Cheryl said something. But I remember I was so, SO angry. I tipped his coffee all over his stupid laptop when he wasn’t looking. I saw the wallpaper of the race car, the icons on the screen and the cup of coffee and I just DID it, tipped the whole cup over the keyboard. He deserved it, and he never came back to our school.

I don’t want to write what happened next, but this is part of a bigger project, and it should be “from the heart”. This is about as “from the heart” as I get. And I promised my dad I’d let him read it, so I must finish it. He took on extra shifts at the factory to pay for me to do this course, so I owe him big time, what with his back being messed up and all that. Here we go…

The very first time Ginevra came down to the Netball courts she sat and watched us play for only a few minutes, then she was on the iPad for a while. Then she tried to speak to Melinda Sanders, our coach. Melinda was only in year 12 but she was a bit of hero to us because she had a car and a part time job at McDonalds. When she wasn’t working the drive-through, she was coaching the Little Grove Under-15 Gems, as she was the Goal Defence in the senior Gems. One day I wanted to be just like Melinda and have a car and a job, but maybe not her gross boyfriend Anton. He was creepy. Ginevra and Melinda had never met but I heard their entire conversation.

“Excuthe me but I think Brodie Marie Regan and Thamantha Rawlingth should thwap plathes.” Melinda looked stunned and then slowly replied, “What did you say?” “I wath reading a netball thrategy on making of the motht of your playerth and thince Thamantha ith taller, she should be Goal Defenthe, not Captain. Bethides, Brodie Marie Regan ith fathter.” I learned to listen around the lisp and understood her right away, but I really didn’t want Melinda to think I set it up. Yes, I was taller than Samantha, and a faster, better player. But it was a big deal that Mr Rawlings, owner of “Rawlings Fine Meats”, regularly bought the netball club items that they needed. When you wear the logo of a person’s livelihood, they own you, unofficially.

But Ginevra didn’t know that. In her world, which was a little black-and-white, there wasn’t room for the very grey situation between Mr Rawlings and Melinda, who kept his daughter in the best position on the team. Melinda, who was never quick on the uptake, took a moment to consider this and said, “No, Samantha’s dad sponsors the team through his business, and he wants her to stay Captain. Thanks, but.”

Looking back, this may have set up the animosity between Melinda, Ginevra and by extension, creepy Anton. Anton’s deepest, darkest secret was that his dad was the scariest person in Little Grove.

Everyone who lived in the area had seen him. They lived near the border of where Little Grove became Ludersfield, on a property that occasionally had a horse, or a really thin goat, but mostly was the home to car-skeletons. To guard these precious, broken-down cars Anton’s dad, Mr Brumdel, kept his dogs.

There were four in total: two darkish German shepherds, a cattle dog with one eye and a white pit bull terrier who had the privilege of being named ‘Killer Jap’. Apparently, Mr Brumdel was in a war or something, because he really didn’t like anyone Asian and was always threatening to ‘sick Killer jap onya’ if you came too close or looked at him wrong. And it seemed EVERYONE had looked at him wrong at some stage. He’d walk these four horrifying dogs twice a day, once first thing in the morning and the other just as the sun was setting. So there were times when we’d be leaving netball and he’d be walking down East Little Lane, filling the path with four insane dogs that were only BARELY restrained by a thick silver chain.

Everyone was terrified of the dogs because they always appeared to be just barely within the control of skinny Mr Brumdel’s tattooed arms. Anton was the only person they never seemed to bark at, of course, but everyone else refused to go near them. I had seen people turn around or cross to the other side of the street in front of cars to avoid being near them.

Except, of course, for Ginevra.

She approached him for the first time last year, in year 7. She told him that his companion animals weren’t “thafe” to walk around the neighbourhood and that dangerous dogs could be put down if they attacked someone. I was a few metres away because I didn’t have the courage to get any closer than I needed to. Killer Jap was snarling at me, and I remember Ginevra staring hard at Mr Brumdel, the way she looked at everyone. I will never forget the hateful slew of words he spewed at her, but it didn’t dampen her spirits. Despite Anton being Melinda’s boyfriend, Ginevra was writing to the council email after email about Mr Brumdel’s dogs. She was determined to see it through and kept telling me, “The law ith on my thide.”

Last school holidays, the Rhodes family took Ginevra to Moree to see her aunt’s family. Ginevra apparently spent the entire summer (thummer?) swimming in the yellow-watered dam until they had to drag her out at nightfall. She also would have ridden around with her cousins Jacob John Rhodes and Harley Elaine Rhodes. Even when I met them, they weren’t ‘Jake and Harley’, I always thought of them by their full names. The Rhodes of Moree presented Ginevra with a beautiful woollen red beret, which she instantly loved. I remember when she wore it to school; sometimes she would rub it on her cheek, or on the sensitive skin on the back of her hand, or on her neck. It was SO not part of the uniform, but the teachers were always very kind when Ginevra HAD to do something, like wearing her soft pyjama pants in the school navy colour, even in summer. The beret clashed, but she loved the texture of it.

She was wearing it the last time I saw her, around 5:30 on a slightly chilly Thursday. We had been training hard after school and Ginevra was happily sitting among our bags reading and occasionally looking up, when she had a phone call. Her mum was going to be quite late to pick her up and dad was still at the studio in the city, so she wondered how Ginevra would get home. Most parents might not have bothered to call but sweet Doctor Rhodes knew that her daughter, my friend Ginevra, would not be ok if there was a change in routine. I knew as much when I saw Ginevra stand up and start tapping the side of her head opposite to her phone. I’d seen her do that for most of my life, it meant she was upset and needed help. I signalled Melinda for a break, and she rolled her eyes and blew her whistle. Like I said, Melinda never liked her.

I jogged over and Ginevra was hitting herself harder now, so I looked her right in the eyes and said, “Let me help.” Still hitting, she passed the phone to me, and I heard Dr Rhodes trying to soothe Ginevra over the phone. It was strangely intimate, breaking into the conversation like that, but I knew them well, so I thought it was ok. “It’s me,” I interjected, and Dr Rhodes soothing voice stopped.

“Brodie thank goodness. Can you walk her home? All the way home?” I knew what she meant, I lived in East Little Grove, the bad part, maybe two minutes away. But the Rhodes family had a lovely, large house just outside of our area, in the much nicer suburb of Barstow Falls. The walk would be at least 40 minutes, maybe more if Ginevra felt agitated.

But I didn’t care. Ginevra was my Friend with a capital, and in that moment, I felt very protective of her. I remember the way she spent her entire savings on the gold ‘Best friend forever’ necklace she gave me, the only gold thing I owned. Sure, Dr Rhodes had tried to pay for it, but Ginevra had insisted loudly that I was HER Best Friend. I ran a finger over the half-heart on the golden chain at my neck and nodded, “Of course I will Doctor Rhodes, of course I will.” She hung up and I reassured Ginevra that everything would be ok. She gave her head one last tap and I did “deep breath”- a gesture we had learnt from Spectrum Awareness Week, and we both took one. She was ok.

Melinda tried hard to get us back on form after that, but our rhythm was gone. Ginevra was fine but it was as if the whole team had been given bad news, so ten minutes later Melinda dismissed us. We were all out of shape she said, and it was true. Six weeks of hard rain had flooded the local sewers, and this was the first day when there wasn’t a slippery, fine mud on the court. Made sense that we should be in poor form.

So, we started walking. I can’t even remember what we talked about, only that it got very cold and dark very quickly. For a while it was nice that it started raining, because I cooled off, but very soon we were soaked. What I DO remember thinking, not for the first time, that I wish my dad didn’t always take the double and be home on time occasionally, but with a pang of guilt I remember that his overtime at the factory was the only thing between us and moving in with my nan in Mollymook. We were poor, there was no other way of explaining it. I always knew there was something different about us, especially compared to my dear friend and her large house. Dr Rhodes would drive me home later and I would be in her beautiful BMW, a very different car to my dad’s rattly old ute. I was deep in these thoughts when Ginevra stopped walking suddenly, because she heard the barking long before I did. It was Mr Brumdel.

Standing in the lane between some of the poorest townhouses in Little Grove is not where you want to be when there are scary dogs nearby, so we started running. It was the worst thing I could have done because I lost sight of Ginevra between streetlights when she ducked into an unfamiliar alley. I started screaming her name, but she had bolted. She’d never been to that part of Little Grove, and the moment we were separated she began to cry this low-pitched sobbing I knew would lead to worse things. Still screaming her name, I started to sprint my hardest. In my running and fumbling, I reached for my phone and dropped it straight into a puddle. I picked it up, barely caring, because her sobbing was like the build-up before a massive crying fit and my heart ached for my scared friend.

I tried to follow the noise, but we were coming up to the massive storm water drain that ran under Ludersfield Road Bridge. It ran behind the dodgy, decrepit houses and I hoped Ginevra had the sense to stop running before she got there. It was where kids when to shoot up or have sex on disgusting, abandoned mattresses that only barely avoided getting soaked by the run-off water. Then my heart stopped when I heard the barking intensify and a terrible scream split the night sky.

I had heard Ginevra scream many times and for many reasons but this scream, the scream from my nightmares, was unlike any of her other screams. It was wild, terrified, and animalistic. Louder than anything I had heard before from her and somehow more desperate than a normal scream should sound. I was breathing so hard, still tired from netball. I needed my asthma puffer, but I forgot to pack it. Then I collapsed to my knees, holding my head as the barking intensified to snarling and the screams abruptly stopped.

I was told I lost consciousness because I somehow passed out. In the moment when Ginevra needed me the most, I collapsed into my own fear and failed her. I just don’t remember how I got there, only that I came to in the hospital. Maybe I hit my head, or just tipped over from shock, between two houses, just meters from the opening of the storm water drain under where the cars pass. There was still a lot of water from the recent rains, and it was flowing as fast as a river. That’s right where they found me, but they did not find Ginevra.

The Rhodes family were very kind and moved away immediately after the funeral. The entire school attended but I wanted to slap them all. They never knew her, not properly but there they were, enjoying a day away from maths because my precious, special friend was now gone. They said she was an angel taken from us in the funeral and tried to draw attention away from the fact that my dear friend was not in the small white coffin. She was nowhere.

These days I have a ‘recurring dream’ that my psychologist (who is free of cost thanks to the school) helps me deal with ‘trauma’. I’m sceptical about it all since I don’t remember, but I have a new fear of being caught in the rain. When its about to start coming down, I hear sounds that I can’t really place, screaming, definitely screaming. Also, the sound of dogs snarling and eating, then the loud splash as something falls, and the laughter. Mr Brumdel laughs in my head, and I hear, “Get her Jap! On ya Killer Jap!”

But it’s only a dream.

He still walks them down the street, every evening. They’re still a snarling, horrifying mass of teeth and muscled, sleek bodies wearing studded collars. But now Killer Jap wears a bit of scrappy, red bandana around his neck.