The grieving family arrived too close to closing time and were forced to say hello and goodbye almost in a single breath. When you live at the cemetery, you learn that the face of sadness can be a mask of confusion when you simply don’t know what to do. These people moved with characteristic indecision, not sure if they wanted to express grief or mask it.

I watched them from behind a nearby tree, noticing everything, as is my habit. The mother held the toddler, confusing the girl with her stifled tears. I see the father, hands in pockets, his posture screaming with reluctance. Only the teenage boy interested me as a curiosity, as he, and only he, bent over to brush debris off the headstone.

I bent low, fascinated now at how these four very different beings moved over soil where their relative was buried. Focusing my senses on them, I probed for answers, and the pictures formed in my mind. The man 6 feet down had been her father, the crying older woman, and I sensed he had never liked this husband she had chosen. Ironically, I felt the same stalwart stubbornness in him, a bonus feeling from being one of the dead who still gets to walk the Earth. Stretching my senses further, I gleaned a wave of guilt from her; she felt she didn’t visit enough, talk enough, do anything quite enough, and now here she was. Too little too late, he would have said, with his taciturn honesty.

Inwardly I rode the wave of guilt she was thinking about, and it crashed to its natural conclusion; she had done all that she could with her children, husband, and job. Even as she silently stared at the grave, the little girl squirmed and began to babble. In the guise of comforting her, the mother buried her face in her daughter’s hair and wept.

The teen boy had been dusting the grave with his sleeve and now traced his finger over the delicate letters and numbers. He did some math. I felt he wanted to confirm that longevity ran in the family, but when he turned to look at his mother, he thought better of it. Instead, he commented to his father that it was a nice headstone and Poppa would have liked its elegant, simple look. He had an eye for detail, that boy.

The father set down the yellow roses and awkwardly comforted his wife while sneaking a look at his watch. Even from my concealed position, I could tell he felt cold and uncomfortable. I resented his lack of interest and focused hard on him, reading as hard as I could. His lifeline was not as long-lived as hers, and I saw many hours in a lonely hospital before he passed. Then, in his final days of half-awake sedation, he would crave his wife’s attention and wonder why his daughter and son do not visit. Something in the vision showed me their divorce and it seemed fair, apt even.

They left soon after, the mother having taken a moment to say something I did not care to hear. When she approached alone, having handed the toddler to her husband, I wrenched my senses away and gave her privacy. It felt wrong to invade that moment, and I will never know what caused her cathartic sobs.

He would never hear it: her father, I mean. Part of my power is seeing where they go, and for this man I sensed a golden, warm light. He dwells in the hereafter I have not yet been to.

I watched the family walk down the hill and back to the car while I drifted to the other part of the cemetery to make a visit of my own.

Since I am neither fully dead, nor fully alive, I have my own way of looking at events like this. Part of me dislikes the empty spectacle of visiting now, when nothing more can be done. But a wiser part of me envies their continuing quest to make something right and repair what is permanently broken. They know it’s futile, but they do it to soothe a part of themselves, the visits being the public balm to private wounds.

I lived long ago, but grief has not changed. These days, people seem to need an audience for everything, and they’d rather connect through their devices than in person, but that was the most notable of changes I had seen. They still wept as they had before. If anything, there was more regret now than I had previously seen and I would know: regret could be my middle name.

I float past graves and markers, stones growing ever older in time from one end of the cemetery to the other. They continue to pass on but there is only so much room for the dead amongst the many buildings for the living. Will the living ever reach a point past polite decorum and insist that burial is too decadent? I do not know how much time I have left, but I observe more and more who chose to be ash in the wind rather than in the soil. Not that I had a choice.

Proceeding to the oldest part of the cemetery, death becomes more grand, or at least the monuments do. She is near the ostentatious angels and gaudy mausoleums families used to be proud of. She could not afford an angel when she died, but the one next to her cast enough of a shadow that she could enjoy that borrowed glory. As is my custom since I found her, I focused my corporeal energy and cleaned the dust from her name plate.

Helen Dorothy Pleasance

13th December 1902 to 5th March 1944

We cherish her always

She was my mother, dead at forty-one and laid here. For many years I wondered about the bird flying out of a basket, so carefully carved by skilled hands on my mother’s headstone, and considered the reasons it was put there. To me, it represents her humble origins, as we were always poor, and how the family worked hard to make something of themselves. But that is one of many questions I would ask if she was still here, the way I seem to be.

Somewhere behind me, the cemetery is closing its metal gates and I sense an impatient guard reluctantly ambling amongst the headstones, but he would never spot me. I let myself fade just enough that he would mistake me, overlook me, and I could continue my version of mourning.

When I lived, from 1922 to 1930, I was one of two happy children, but as the oldest, and a girl, I had to be sold when the family was at its poorest. The farm, once a source of food and life, had turned to dust and my parents were desperate. I remember a vague argument about having land, precious land, but unless the children could eat dirt, there was no value in it.

I was only eight. My brother was merely two years younger than me, but he was the greatest achievement of both my mother and father—there was no chance he would have been made to suffer—that’s not why golden boys are born. No, when The Gentleman took an interest in buying me from my mother, there was only a brief hesitation and then, I’m sure, relief.

My mother and father worked it out and I was sold for an envelope full of money. Is it good that I do not know how much I was worth? If I could sleep, it would be harder to close my eyes at night knowing the paltry amount. Better that I just remember the moment I stood with a wooden box of possessions on the front step. Then he takes my hand and leads me away. I realised too late that I will not be going back.

Certainly it could have been worse, I know that. I was never a big talker; instead, I listened, and many times I heard maids and cooks talking about children sold to be playthings of older men and women or sent to work in dangerous factories to be horribly mangled. When I lived with my parents, I saw my mother burn her hand on the stove and to me, that is all factories were: giant stoves that could sizzle the skin right off the bone. At least I was not sent there. I spent a lot of cold nights in the servants’ quarters and went to bed hungry, but yes, it could have been worse.

I was fortunate to have become a maid and companion to the Gentleman’s daughter Marjorie Elsemore, until we were playing in a river and I drowned on a spring afternoon.

We’d been playing, squelching in mud, pushing each other happily and daring each other to go further and further toward the middle of the river where our feet no longer touched the bottom. I was winning because I was taller, but I could not fight the strange pull that dragged me under when I went just a little further in than Marjorie had. I crowed with joy that I was braver, “Queen of the River!” I yelled, but then I lost my footing and the game ended. Well, the river had been playing its own game and I lost that day.

I knew something was wrong when an instant later (it seemed), I was looking at my body from the edge of the river. I could see myself floating down the river as Marjorie screamed herself hoarse and eventually, someone came to get me. Confused, I tried to touch my hands, my hair, the water, but my fingers passed through as if I was made of air. Marjorie could not see me, but I could see them, all of them who came to help. I had never in my life been so popular as I was moments after death.

They tried to shield Marjorie, but bless her, she cared for me and was very upset. When I concentrate, I can hear her howls clearly. Over time, I’ve watched her grow into a fine woman who made her family proud. When I am not here, I visit the facility for older people where she lives, my dear friend, and I try to watch her without giving her fright. She is still as elegant and stately as ever, age having not taken her dignity yet, and I feel a strange pride for having been there when she was just a little girl.

Her family honoured my passing by burying me in a quiet corner of the Elsemore gardens, amidst deceased pets of Marjories, near a stone bench she would often sit at. It is a beautiful place I have only visited once. It is full of life now and constantly busy as the house has been turned into some sort of hotel. People have even been married at the river bank right near where I died and if I had a voice, I would laugh.

So, dear reader, why do I come here? When the world is available, why keep returning to this cemetery and its tidy rows of strangers?

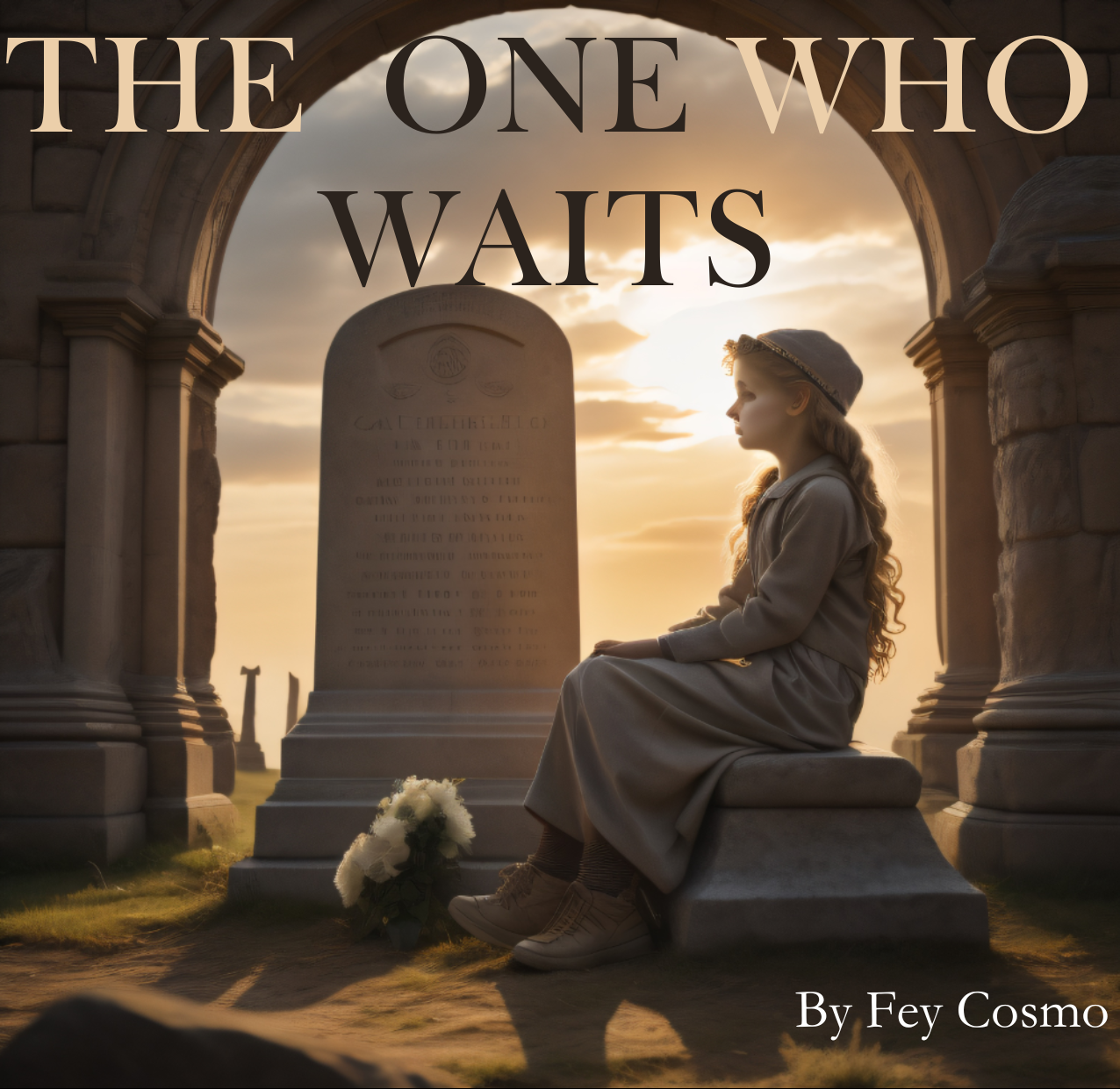

I will answer, as I sit as before her grave. I am waiting for my apology.

I will wait until the day Helen Dorothy Pleasance returns from her personal, golden heaven and says, “Sorry for selling you.” I want to hear her say, with tears in her eyes, that she was wrong to trade me, because I was not a commodity: I was her child.

I wait, and I wait. I have waited more than the fifteen thousand days she lived.

I am determined to remain until she returns. In my mind’s eye, I see her running towards me instead of walking away. I hear her calling me to her open arms instead of turning her back to me. And rather than accepting politely with downcast eyes, she proudly spurns the money. “No amount of money is greater than my love,” she will say, and she will wrap me up in herself as only she could, saying, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry.”

The moon will rise and find me waiting, patiently upon the spot where her earthly remains rest and I wait for the afterlife that is the sound of her voice.

- From Tabletop to Digital: The Evolution of RPG Games

- Reverse Railroading GM Technique

- Flowers For The Lady

- The Sounds of Little Grove

- Rois: A tale of medieval horror

Actual play podcast Afterlife All the feels app for RPG equipment Attack descriptions Barbarian talk Barbaron monolog Combat Combat ideas Cult D&D spell Arcane Ward D&D spells Demons Dragons Dungeons and Dragons Fiction FictionFairy Fiction Fairy Fighters Ghosts gm tips Gore Horror How to play a Barbarian Kids and RPGs make the fight less boring Non-Combat Scene Ortug Ortug RPG Advice How to play a Barbarian Ortug the Barbarian Ranger spells roleplaying tips RPG advice RPG games RPG podcast RPG Pranks RPGs for kids Sci Fi Scifi podcast Serial Short Story Star-Fall RPG Podcast Sword drawing app why kids should play RPG Games Witchcraft